As a research fellow and powerlifter, I naturally found parallels between my academic mindset and the world of competitive lifting. Powerlifting, a sport involving three core lifts—squat, bench press, and deadlift—demands not just physical strength but also continuous learning and adaptation. This is where I have applied the Action Learning Cycle, a concept I regularly use in my academic and managerial roles, to enhance my performance in powerlifting.

Application of Action Learning in Powerlifting: A Case Study

The Action Learning Cycle in Management and Research

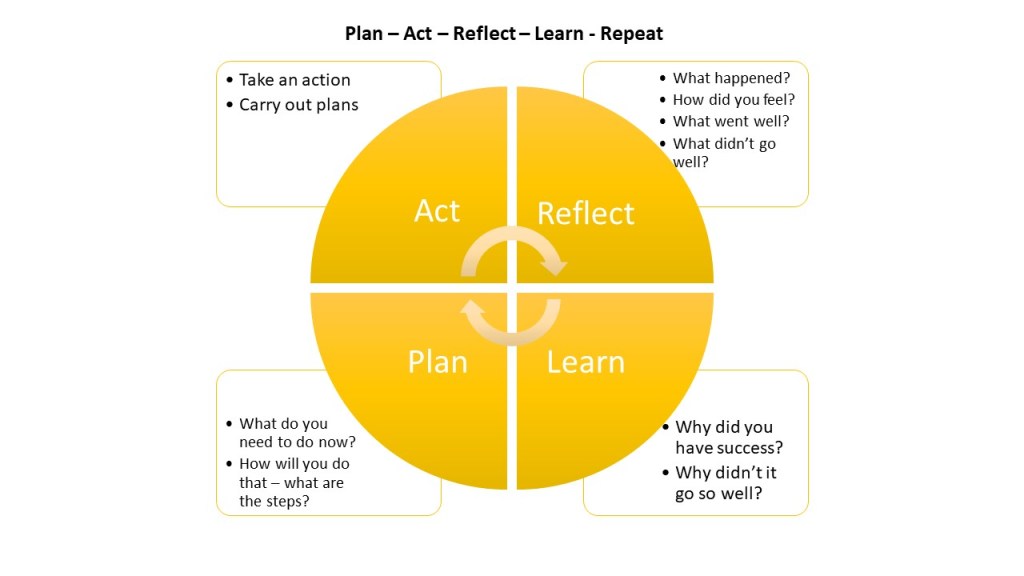

Action Learning (AL) is a systematic approach to problem-solving that integrates action and reflection, driving continuous improvement. It was first introduced by Reg Revans in the mid-20th century and has since become a widely adopted framework in management and organisational development. According to Revans (2017), the key elements of AL involve real-world problem identification, group collaboration, action taking, reflection, and iterative learning. This reflective practice enables individuals and teams to tackle complex and “wicked” problems—issues that are difficult to define and even harder to resolve (Grint, 2010). Through action and subsequent reflection, new insights emerge, which then feed back into the planning stage, forming a cyclical learning process.

The AL approach has been extensively applied in sectors ranging from private business to public administration (Pedler, 2012). In these contexts, teams often confront intricate problems that require adaptive and systemic thinking. For example, Pedler and Abbott (2013) emphasise the effectiveness of action learning for leadership development, fostering an environment where problem-solving is deeply reflective and practical.

Translating Action Learning to Athletic Performance

Drawing from this well-established methodology, I have applied the Action Learning Cycle to my powerlifting journey. Just as AL in management requires problem identification, collaboration, and iteration, athletic training benefits from similar practices: planning, execution, reflection, and learning.

- Planning Action (Plan): Before each training session, I record my objectives in a training journal. These objectives are specific to each lift, with particular attention paid to weight progression and form. This stage parallels the problem identification and action planning phase in AL, where the initial goal is defined and prepared for execution.

- Taking Action (Act): During training, I perform the prescribed lifts, ensuring to capture them on video for later analysis. This execution phase mirrors the “taking action” step in AL, where planned actions are carried out in real time.

- Reflecting (Reflect): Post-lift, I engage in a reflective process. This step is crucial, as it involves assessing multiple dimensions: technique, speed, form, and subjective feelings of difficulty. According to Schön’s (1991) theory of “reflection-in-action,” this real-time self-assessment is a powerful tool in developing professional competency. In the case of powerlifting, reflecting on how the body feels under different loads—whether it is feeling strained or efficient—provides invaluable feedback that informs future action.

- Learning from Results (Learn): Finally, I analyse the factors contributing to the success or failure of each lift. Was the lift heavy because of inadequate sleep, poor nutrition, or suboptimal timing? By asking “why,” I dig deeper into the variables influencing performance. This process closely follows the AL method, where learning is extracted from the outcomes of action. For instance, Senge’s (2006) work on “The Learning Organization” suggests that deep reflection fosters a culture of continuous learning and improvement—a philosophy equally applicable to individual athletic training.

Complexity in Powerlifting: Beyond the Simple Mechanics

While powerlifting may seem straightforward to an observer—lifting weights in a specific sequence—it is, in fact, a highly technical and mentally demanding sport. Elite powerlifting requires not only physical strength but also nuanced motor control, psychological resilience, and detailed attention to recovery and nutrition. According to Enoka (2008), the human neuromuscular system operates with extraordinary complexity, and minor deviations in form or mental focus can significantly impact performance.

Moreover, the body’s responses to training stimuli are influenced by a multitude of factors, from hormonal fluctuations to psychological states (Kraemer & Ratamess, 2005). For example, the interplay between nutrition, sleep, and cognitive stress directly affects athletic output, making consistent performance challenging to maintain. These variables often mirror the “wicked problems” found in management that Revans highlighted—complex, multifaceted issues with no clear solutions.

Research in sports science has demonstrated that performance variability is common, even among elite athletes, due to the unpredictable nature of human physiology (Smith, 2003). Therefore, adopting an AL approach enables me to continuously learn and refine my training regimen, adapting to the ever-changing demands of competitive lifting.

While the broader scientific community continues to explore the mind-body connection in sports, powerlifters and athletes alike can benefit from structured self-reflection and adaptive learning. In the absence of complete scientific explanations, action learning remains a practical and evidence-based method for improving performance, allowing athletes to engage in iterative self-improvement based on real-time feedback.

Conclusion

By integrating the Action Learning Cycle into my powerlifting practice, I have been able to approach training with the same strategic mindset that guides my academic research. The reflective and adaptive nature of AL allows for continuous performance improvement, even in the face of the complex physiological challenges inherent in powerlifting. As more research explores the complex relationships between mind, body, and performance, action learning offers a robust framework to navigate these uncertainties and drive meaningful progress.

References

- Enoka, R. M. (2008). Neuromechanics of Human Movement. Human Kinetics.

- Physiology. 70, 367-372

- Grint, K. (2010). Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: the role of leadership. Clinical Leader, 1(2), 11-25.

- Kraemer, W. J., & Ratamess, N. A. (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 35(4), 339-361.

- Pedler, M. (2012). Action Learning for Managers. Gower Publishing Ltd.

- Pedler, M., & Abbott, C. (2013). Facilitating action learning: A practitioner’s guide. Management Learning, 44(3), 207–222.

- Revans, R. W. (2017). The ABC of Action Learning. Routledge.

- Schön, D. A. (1991). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Broadway Business

- Smith, D. J. (2003). A Framework for Understanding the Training Process Leading to Elite Performance. Sports Medicine, 33, 1103-1126.